BAN ON IMAGE

Installation, as part of Silent Voices, a group show at the St Petersburg Museum of History, National Center for Contemporary Art & Pro Arte, Sept - Oct 2017

“You could say we are heroes here in Leningrad, but what kind of heroes are we then? During the first months, people were still moving, hiding in the shelters, still had energy. We were probably heroes back then. We led lives devoted to the country and were eager to crush the enemy. But now the radio is silent and we do not know what’s going on in the country. We get no newspapers or letters and live in complete darkness. This darkens our day by day. Like doomed people, we no longer react to anything and await death to relieve us from the nightmare of reality. It’s obvious we are being sacrificed for the sake of the country.”

(From a letter intercepted by Soviet military censorship)

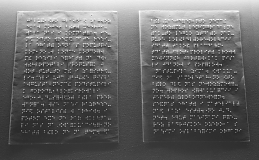

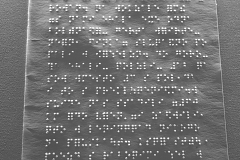

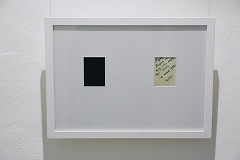

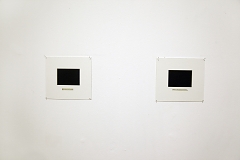

Max Sher’s installation creates a different model to represent the 1941–44 Nazi siege of Leningrad – on the one hand, a more humane one, focused on the everyday, and, on the other, one requiring doubt and effort. Banning images is one of the oldest methods of submission. Power relies on it to deprive human beings of their most important capacity and possibility – to get a sense of what is going on around them, because they cannot do so if there are no images. The Ban on Images project investigates this phenomenon with regard to the Nazi siege of Leningrad. An enemy encirclement – tragically real in the case of the siege of Leningrad, or taking the form of a political metaphor in other cases – can serve as a pretext for introducing a ban on images. The result of this particular ban was an almost complete absence of private visual evidence of the siege: the photos everyone has seen were produced by war photographers employed by and acting on behalf of the Soviet state. During the siege, photography without permission was banned, and it became illegal to possess city maps, postcards with views or travel guides, while private diaries or letters could be used as evidence for criminal prosecutions if they contained language that could be interpreted as anti-government. The installation includes fragments from the diary of a blind man describing the beginning of the war and the siege. This diary was first written in Braille and then translated into Russian. While working on his project, the artist asked a historian from the Russian Blind Association to rewrite it in Braille. In the diary, its blind author uses a metaphor of vision (“before our very eyes”), raising the question of trust in evidence. Another question also arises about the inevitable “intermediaries” (historians or translators, for example). It is also a powerful statement on the impenetrability or unreadability of a true piece of evidence. Only a blind person can read this text; the sighted can touch Braille, but won’t get anything out of it. In the same way, any situation of horror can only be genuinely felt when you are in it yourself. A sound cabin broadcasts the texts of political statements by people inside the besieged city of Leningrad, overheard and recorded by secret police informers in the form of “special reports on public sentiment”, as well as the texts of anti-government leaflets that circulated in the besieged city and letters intercepted by censorship. These are the restored voices of people who encountered a ban on images, when irregular government messages were the only available source of information and food for reflection. The question of evidence is raised here yet again, only from a slightly different angle: in what form and how do these testimonies reach us today? Judging by the literary character of the texts, they have most probably been edited or even invented by the NKVD secret police, then passed onto their Moscow bosses, then selected in the archives and published by a historian (Nikita Lomagin in this case, who published these documents in his book The Unknown Siege of Leningrad), then again selected by the artist and processed through a voice reproduction system. The voiceless are thus reclaiming their voices, but only after editing and selections spread over a period of time. A mirror in the cabin before the listener serves to remind us that any perception of history is always individual and is influenced by the worldviews, political convictions and other features of an individual’s vision. In the room, all the voices blend together into a muffled cacophonic clatter. Another piece in the installation is an original photograph found by the artist a few years ago in a private archive. It was made during the siege (the date and the place are marked on the back – “L[eningra]-d, July 1942”). Technically, it’s a forbidden image – photography without permission and owning cameras were prohibited during the siege. It means that it was a private violation of a state ban for the sake of love and memory (the inscription on the back was an obvious dedication to a loved one: “My dear Fyodor, here’s yet another wife for you”). One private photograph destroys all the mainstream visuality created by the state to represent the siege. The photo and its back are deliberately separated, so as to make it unclear whether the dedication really relates to the picture, whether one can believe that the photo really was made during the siege, and how perception changes when looking at an image without a text and at a text without an image. Photo captions cut out from a pre-war Leningrad travel guide constitute the fourth element in the installation. They refer to yet another ban set in place during the siege – all travel guides, maps, postcards with city views and photos had to be handed over to the NKVD political police. There was also a tacit ban on asking strangers for directions. The viewer is thus invited to imagine some of the city’s landmarks using only captions cut from the images. Finally, there are several landscape images of St. Petersburg created by the artist in 2013. They reproduce the format and style of amateur photographer Alexander Nikitin (1907–1942). In March 1942, Nikitin was arrested by the political police on a Leningrad street and quickly sentenced to five years of hard labor for taking pictures without permission, that is, for violating the ban on images, although he was formally charged with “counter-revolutionary propaganda”. He died in prison that same year. After WWII, his conviction was recognized as unlawful and politically motivated by a Soviet court. Alexander Nikitin’s story served as the starting point for Max Sher’s three-part project – Map and Territory (Triumph Gallery, Moscow, 2014), Surface of Writing (a collaboration with curator Alina Belishkina, Vertical Gallery, St. Petersburg, 2015), and now Ban on Images.